Scaling Urban Agriculture: Completing the Financial Sustainability Cycle

Financial Sustainability Series | Part 4: From Accountability to Reciprocity

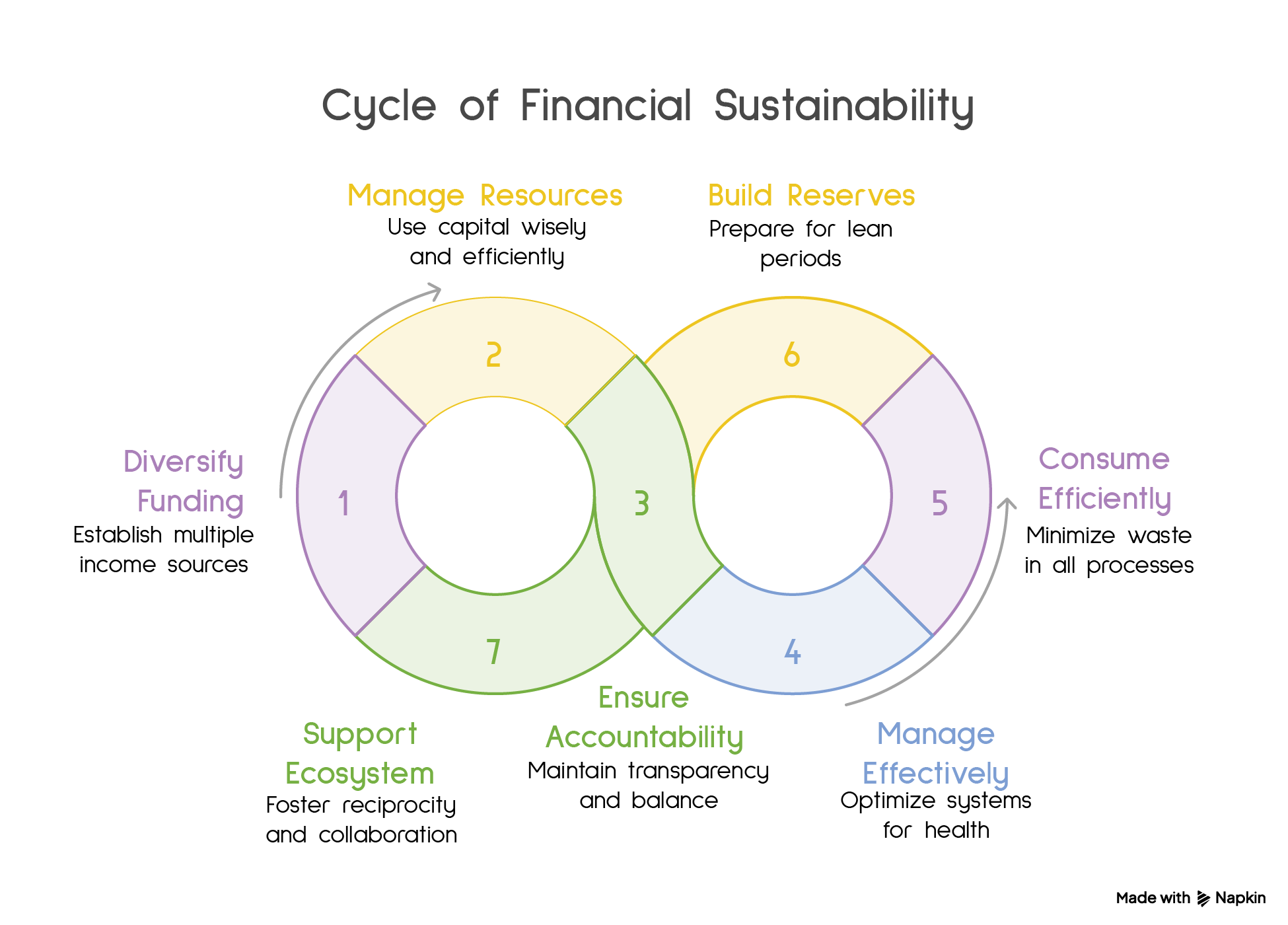

In the first post of this series, I introduced the financial sustainability cycle.

Its components operate as interconnected flows:

Diverse funding streams – like biodiversity, diversity strengthens resilience.

Responsible stewardship of resources – managing capital as carefully as soil fertility.

Accountability – transparency that keeps the ecosystem in balance.

Effective management – tending and pruning for optimal health.

Efficient consumption of resources – minimizing waste.

Reserves and contingency plans – storing energy for lean seasons.

Reciprocity - Attracting and providing support to other members of the ecosystem.

In the third post, I started to dive deeper into the first four components: diversity, stewardship, accountability, and effective management. Before continuing the cycle with efficient consumption of resources, reserves and contingency plans, and reciprocity, it’s worth revisiting components 3 and 4 – Accountability and Effective Management – because they are mechanisms that allow the rest of the cycle to function.

Component 3: Accountability

As an organization grows, staff specialize in their work – program delivery, crop production, engineering, sales and marketing, research & development, talent and culture, and finance – and their view and understanding of the operations of the organization narrows. Often silos develop and teams make decisions with unintended financial consequences. Transparency and accountability are key to overcoming the shortcomings of specialization. Accountability from a financial sustainability perspective requires financial literacy.

Providing consistent, understandable information about the revenue and expenses of the organization on a regular basis is just the start. Teams must understand the full cost (direct + indirect costs) of the programs, products, and services they deliver. Some products may be loss-leaders while others are cash cows – teams need to know which is which and why. Teams must understand terms like return on investment, days sales outstanding, working capital, and cashflow. Teams must understand the financial implications of their decisions on the overall financial health of the organization. This requires training[LR1] , space for questions, timely responses, and shared agreement on what success looks like.

But understanding of internal operations on the finances is not enough.

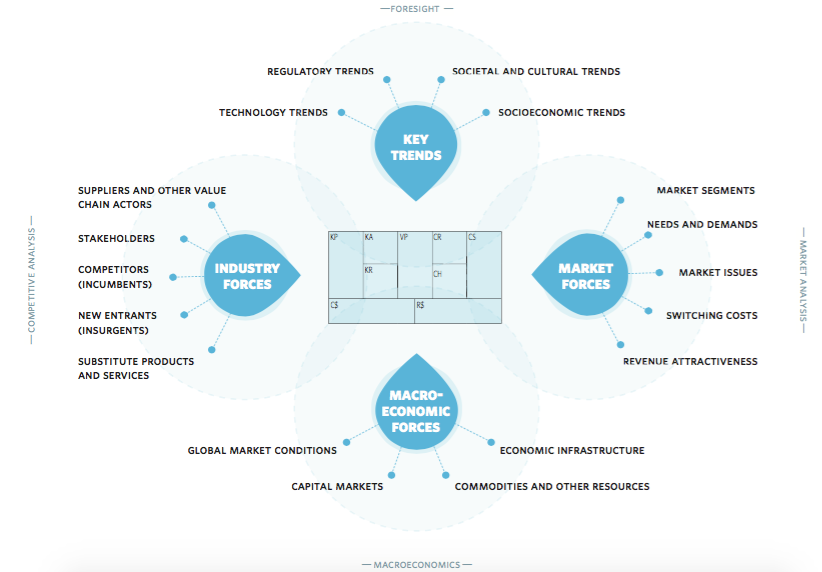

The authors of the Business Model Canvas recognize that business models are dynamic – constantly evolving in respond to external forces. These forces are grouped into four categories: market forces, macroeconomic forces, industry forces, and key trends (see the image below). These forces impact the financial sustainability of an organization. Based on the nature of their work, teams will have insight into some of these forces, not all. Cross-team communication is vital to understanding how geo-political tensions might impact the prices and availability of key inputs to manufacturing or how cultural trends might impact demand for products and services.

Accountability - internally (to your board, team, or partners) and externally (to customers, donors, and community) – helps keep systems in balance. It builds on stewardship by turning financial data into information in the form of dashboards, analysis, and evaluations that guide better decisions.

Component 4: Effective Management

Drawing from multiple disciplines, adaptive management has been used for decades as a strategy for natural resources management. The USDA USDI 1994 Northwest Forest Plan proposed a four-phase cycle for adaptive management – plan, act, monitor, and evaluate. Modern versions present it as plan, act, learn, and adjust.

Plan - Many years ago, a mentor gave me this sage advice – ‘Go slow to go fast’. It means take the time to do your homework - due diligence, feasibility studies, benchmarking, market analysis, pilot projects, and plan – then you’ll be able to proceed and avoid costly mistakes, predictable roadblocks, and rework, which inevitably slow you down.

It is at this stage that you clarify strategic mission and financial outcomes, select policies, strategies, and actions to achieve those outcomes, and establish outcome-aligned measures and metrics. Throughout the planning process, maintain a clear focus on who you are serving – customers or clients, investors, distributors or retailers, the general public, or regulators.

Act – With clear roles and responsibilities, implement the plan.

Learn – Gather information about the work underway – Are things going as intended? If not, why? Are metrics being achieved?-If not, why? In this phase, you observe and collect data to determine if things are going to plan or if you need to adjust.

Adjust – Based on what you’ve learned, you adapt to the facts and circumstances to achieve balance and make progress toward strategic outcomes. This may require pruning: sunsetting programs that drain resources.

Continuing the Cycle

Component 5: Efficient consumption of resources

Through effective management waste of time, labor, materials, and money is reduced. Just enough resources are consumed for the desired result through thoughtful, intentional design of work processes and systems. Efficiency is not about scarcity – it’s about alignment between effort, resources, and outcomes.

Component 6: Reserves and contingency plans

If just enough resources are consumed, there are resources available to store for later. Much like plants store energy in their roots before going dormant in the winter, efficient operations store financial resources for use during lean times. Storing financial resources, reserves, is what allows an organization to continue during the unexpected rise in costs or loss of a revenue source.

From a financial sustainability perspective, a key strategic goal is the building of reserves.

There are two types of reserves an organization should intentionally build – operating and non-operating. Operating reserves are generally three to six months of operating expenses, more if there is more risk of external forces causes disruptions to revenue or prolonged increases in expenses. Operating reserves are the ‘rainy day’ fund that provides cash flow to keep the organization going during tough times.

Non-operating reserves is the long-term savings for buying new equipment, maintaining existing equipment and buildings, and investments in new programs, products, and services. The prevalence of credit makes it temping to spend money an organization does not have yet and become – highly leveraged – a large amount of debt when compared to assets and/or equity. Many organizations fail under the weight of too much debt.

To determine how much the reserves should be, create multi-year budgets and perform scenario planning - What if a major investor calls the debt early? What if a major donor decides to support a different cause? What if a key piece of equipment fails and repair costs are high?

Component 7: Reciprocity

The final component of financially sustainable organizations is giving back more than consumed - reciprocity. Often hard to quantify, reciprocity builds intangible reserves (goodwill, loyalty, and commitment).

Staff give their time, talent, and loyalty – give them a living wage. Consumers give their hard-earned money – give them fair pricing and a consistent, quality product. A community gives you resources and a market, give them a commitment to be a good citizen – support local causes and share resources. Collaborate instead of competing with other organizations trying to achieve similar results.

Conclusion

When accountability and effective management are in place, organizations can operate efficiently, build reserves, and engage in reciprocity with other valuable members of the ecosystem.

Across this series, we’re explored financial sustainability as a continuous cycle rather than a destination – one that mirrors the dynamics of a healthy ecosystem. Throughout the cycle, organizations gain the capacity to adapt, invest, regenerate, and respond to disruptive forces – they become resilient and their operations sustainable.

Whether you are stewarding an urban farm, managing a food hub, running a nonprofit, or building a mission-driven enterprise, financial sustainability is not about doing more with less. It’s about designing systems that work in balance.